American Energy in the 21st Century – A Cautionary Tale of sentiment ahead of strategy

Energy in the 21st century won't look the same as recent history: best to prepare for that, rather than cling to older models

You can check out any time you like, but you can never leave, (The Eagles, Hotel California)

—------------

Note: this is a long piece, about 6,000 words (25 min read).

But it is long-form to place a number of numbers, ideas and predictions in one place, and they inter-link.

The reader can duck out at any point and come back - I may elaborate a section in a future post too.

To help though, there is a 2 page exec summary, which I think captures the main issues, and the main piece is broken into three parts.

Global Energy Interdependence and US Fossil Fragility

China’s Renewable Ascent - the world’s first electrostate

US Energy Choices: Petro Culture vs Energy Tech Leadership

There is also a link here to a previous substack note, focussed on the global power sector for the 21st century which partly covered these themes too.

Those themes were part cliche and part provocation: necessity invents, (China), exploiting your natural resources (OPEC), and being lost in - seeming - abundance, the US.

Its subtitle was - make baby make, don’t drill baby drill. You get the drift.

In essence this piece outlines the idea that energy this century will be dominated by new technologies and products, many of which are being built around us, but many countries will likely cling to the older model of extracting fossil resources to the maximum.

The leaders will reap the benefits of manufacturing learning curves and ever lower prices: others will continue to see reservoirs decline and deplete, never to return.

Today, options remain.

But - this post looks at the (very different) choices being made now by the US and China, and the implications for the long term.

Executive Summary

The global energy system is a web of interdependence, where genuine fossil fuel independence is a myth.

The US, despite its shale-driven export surge, remains tethered to this intricate world-wide fossil system.

At the same time it is now in danger of isolating itself from the large and rapidly rising renewable energy industrial economy.

Key insights:

America’s Fossil Fuel Fragility:

The US is not a petrostate but operates with a "petro-culture," clinging to fossil fuels despite structural vulnerabilities.

Shale oil (notably the Permian Basin) drives recent export growth, but reserves are finite, declining rapidly (15–20% annually), and require constant and increasingly expensive investment. The US also remains a net crude oil importer, highly reliant on Canada’s heavier grades.

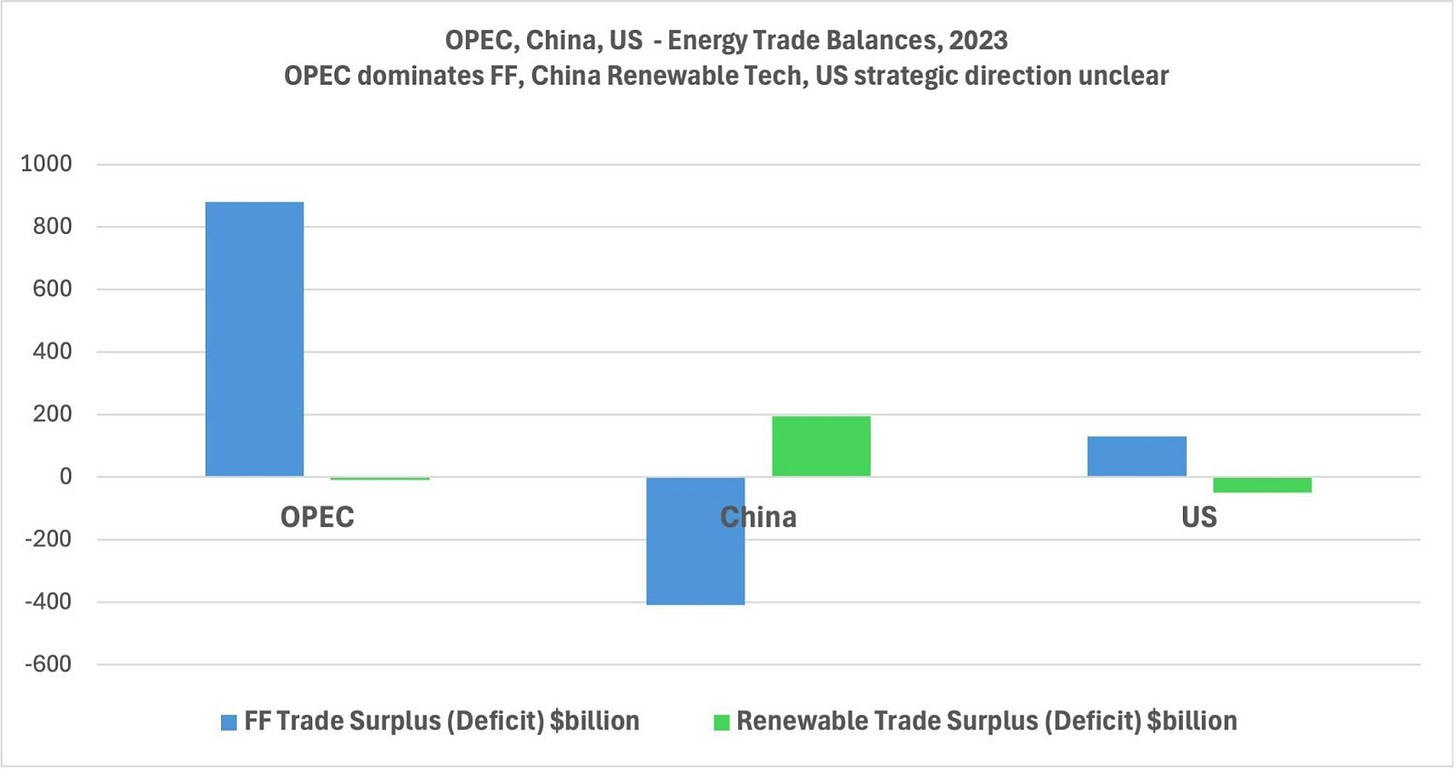

Its aggregate fossil fuel trade therefore yields a modest $130B surplus (5–6% of total exports), but very high domestic consumption (gas ten times, and oil five times per person compared to China) locks in dependency from external sources.

Shale’s fleeting boom masks structural weaknesses: refining relies on imported crude, and LNG exports hinge on volatile global prices.

China’s Renewable Pivot:

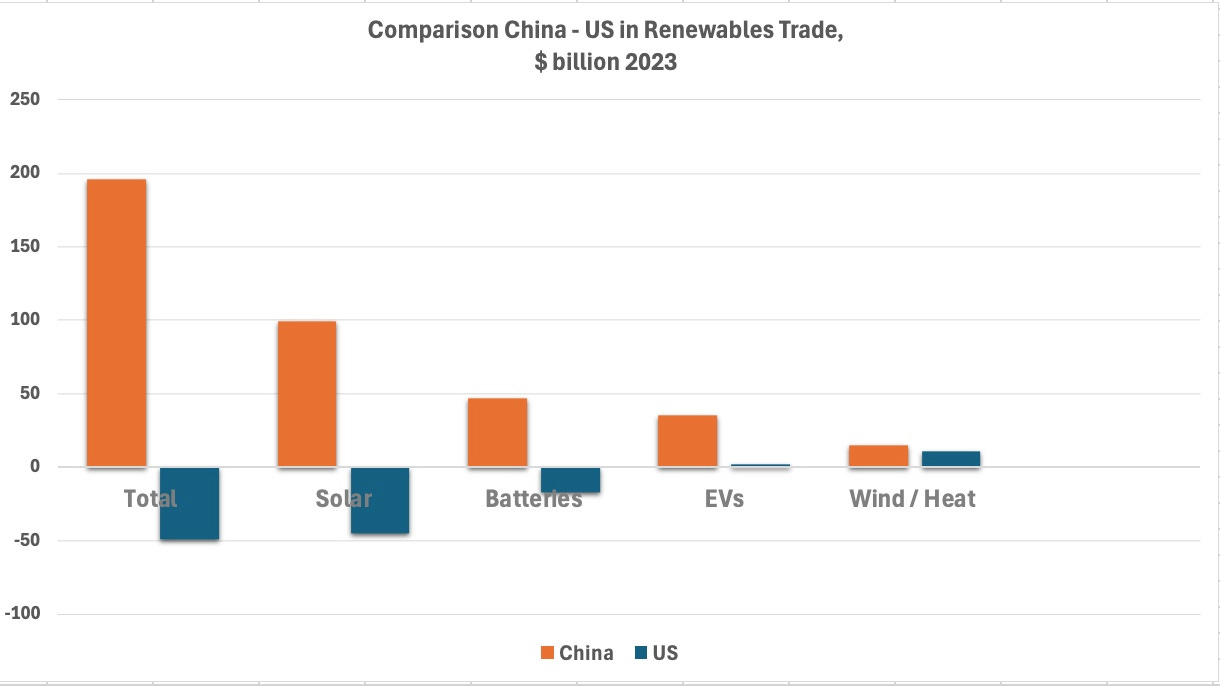

China, burdened by $400B in annual fossil imports, is aggressively building a renewable industrial base. It now leads solar, batteries, and EVs manufacturing achieving a $195B trade surplus in renewables—offsetting 50% of its fossil deficit.

Dominating 80% of global solar panel and 60% of world battery production, China is displacing fossil reliance with scalable, low-cost technologies.

By 2030, China’s renewable exports could eclipse its fossil import costs, cementing its role as the world’s first “electrostate.”

US Strategic Energy Drift:

The US clings to a “petro culture,” prioritizing short-term fossil gains (e.g., LNG exports) while neglecting systemic risks. Renewables contribute just 1–1.5% to GDP, with heavy reliance on imported tech (solar panels, batteries).

Policy incoherence—tariffs on allies, underinvestment in domestic renewables, and Permian overexploitation—threatens long-term energy security and undermines renewable investments.The US already holds a $49B renewables trade deficit, relying on imports for solar panels, batteries, and EV components.

Without rapid action, the US risks reverting to net energy importer status by 2030 as shale reserves dwindle, while ceding leadership in the $2 trillion+ global renewable market.

Converging Crises:

By 2028-2030, the US faces a dual trap:

Flat or declining shale output forces renewed fossil imports, while lagging renewables manufacturing deepens dependency on foreign tech.

This leads to the threat of energy Insecurity: renewed reliance on OPEC+ as well as Canadian oil and gas, and vulnerability to price shocks

And in addition technological Isolation: marginalization in global energy manufacturing supply chains dominated by amongst others China/EU.

Economic strain, job losses, and energy inflation loom.

Conclusion: The High Cost of Sentiment

The US energy strategy is a cautionary tale of mixing industrial energy strategy with emotion

Unlike OPEC’s oil reserves or China’s renewable industrial policy, America lacks a coherent vision. It is neither a petrostate nor an electrostate—nor even a hybrid, clinging to fading shale fortunes while ceding the future energy technologies to others.

Its actions via the IRA and CHIIPS act now seem hesitant, and Canadian annexation ideas and sea-bed trawling for minerals appears performative and show-man-like rather than a well-studied and disciplined industrial energy strategy.

Its fossil powerhouse, the Permian, faces near-term eventual decline. Without urgent investment in renewables, the US will re-enter an era of energy insecurity, hostage to world fossil fuel prices and energy manufacturing supply chains. Tariffs and fossil-centric policies may actually accelerate this decline, insulating neither prices nor jobs.

China’s lesson is clear: necessity drives invention. For the US, the choice is stark—double down on a fragile fossil energy system, or reinvent itself.

The window is closing. By 2030, the global energy transition will be irreversible. If the US remains a sentimental bystander, it risks not just losing energy leadership but wider economic decline.

In energy, as the Eagles warned, you can check out any time you like, but you can never leave.

The bill for indecision will come due—and it will likely be steep.

American Energy in the 21st Century – A Cautionary Tale of sentiment ahead of strategy

1 - Global Energy Interdependence and US Fossil Fragility

Let’s start with an aphorism that we’ll work hard to justify.

In energy, there is no independence if you have lots of fossil fuel: the only route to 21st century energy independence is if you do not have much of them: necessity invents.

Maybe a Chinese cookie bit of wisdom?

Funnily enough, read on.

With the above quote in mind, we are going to focus on the American energy situation: where it stands today, and what its strategy is for the future.

We’ll look at the US relationship with its traditional base of fossil fuel, and in the second half pivot hard to the new energy system of renewable energy technologies, and analyse the US (and Chinese) outlook in this very different energy world.

Before all that, let’s start with the global fossil fuel energy system, start with oil, widen to gas and oil products and then drill down on the US state of play.

Oil: an intricate interdependent web of pipes, storage, boats and money

The world fossil fuel energy system is almost a century old, and so it has laid down a large sprawling global infrastructure of pipelines, storage facilities, and marine vessels to transport it all.

On top of that physical network , it has created a large financial trading system that allows those who have excess oil and gas to sell it to buyers who do not have enough oil and gas to meet domestic needs, or wish to trade it.

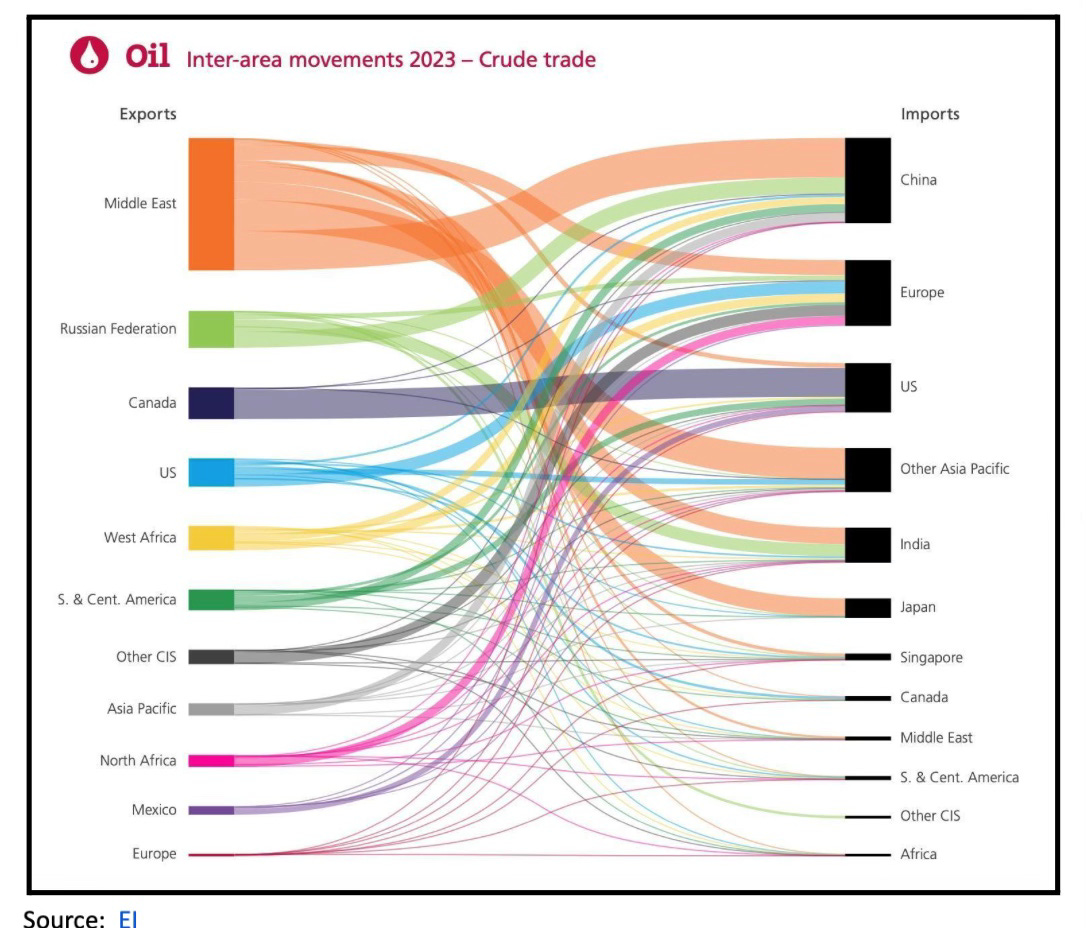

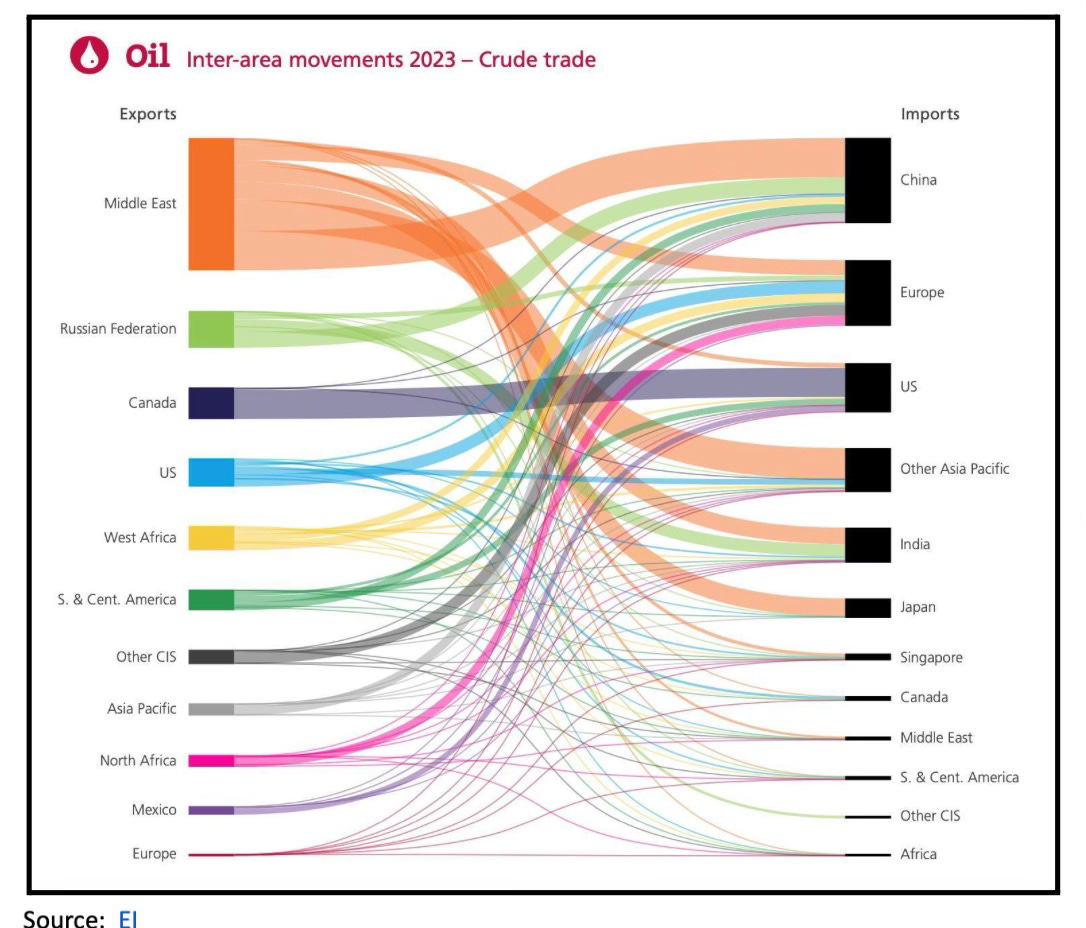

Considering oil, the world produces about 100 million barrels a day of oil, consumes about the same, and trades around 40%, or 40 million barrels per day, from those that have it to those that need it. The rest is managed locally.

This is a big trade effort, about $900 bn is spent on it every year at today’s rates which is set by international benchmarks such as Brent crude, or the slightly cheaper West Texas Intermediate (WTI) oil, created by shale deposits.

Today 75% of all countries in the world are net importers of oil.

Of the remaining 25% only a handful dominate net exports: they are household names, as they have led exports for over 50 years: the organisation of petroleum exporting countries - Saudi Arabia, Iran, Iraq and others - (OPEC) which now also allies with Russia (OPEC+).

OPEC plus Russia supply over 50% of world oil via their exports.

They can do this, because of two factors that few other countries have.

They have very large oil fields and oil reserves, and they have limited domestic demand due to either small populations and / or economies that are under-developed.

The GDP per person in OPEC states is for example 6% that of the US.

This leaves them a lot of oil available for export.

Turning to importers, three dominate: almost two-thirds of all the world’s oil is supplied to China, the EU, and the US. For two of them, they are the opposite of the OPEC situation.

China and the EU have very limited oil and gas reserves and production, so are heavy oil import dependent as they have advanced economies, large populations and hence very high energy needs. Together they consume 50% of world oil.

The third big net importer - the US - is unusual as being large on both sides of the oil export and import ledger, with 9% of global exports, but 15% of global imports.

Keep this in mind for later - it is the essence of their energy conundrum.

If all this feels as much fun as learning multiplication tables , then here is a picture to make it all very clear.

It summarises the web-like nature of oil interdependencies appropriately in a flow diagram (a Sankey chart ): from left to right there are the export flows dominated by OPEC + Russia (and Canada - we’ll come back to that), and on the right the import requirements dominated by China, EU, US.

At your leisure you can then trace all the various flows from each side to the other having taken decades to build - remembering it all adds up to 40 million barrels of oil per day bought and sold, about $2.5 billion changing hands every 24 hours.

The key take-away is that a world energy system built like this creates a vast web of interdependency: the big exporters need many buyers to survive: and all the buyers need the exporters to provide the oil.

If all this seems obvious, here are three key implications of this current oil energy reality:

Fossil fuel energy independence and self-sufficiency is a myth: to achieve it means to have the perfect balance between what you require and what you produce, indefinitely. Even large exporters are dependent - on buyers of their exports.

The oil system only survives via trade: oil, though a commodity, is difficult to store and complex enough to require back and forth contracting to optimise local technical grade selection and production. And as oil prices are set internationally, everyone has to respond by interconnected trade protocols and contracts.

Most importantly, those importing countries (big and small) who have a strategy of reducing import dependence run an increasing chance of exploiting alternative energy options: those that do not, run the high risk of a passive long-term dependence on fossil fuels, a game only very few can benefit from economically, and security-wise, long term.

The scene set, let’s look in more detail at America.

The US - not a petrostate: but a petro state of mind.

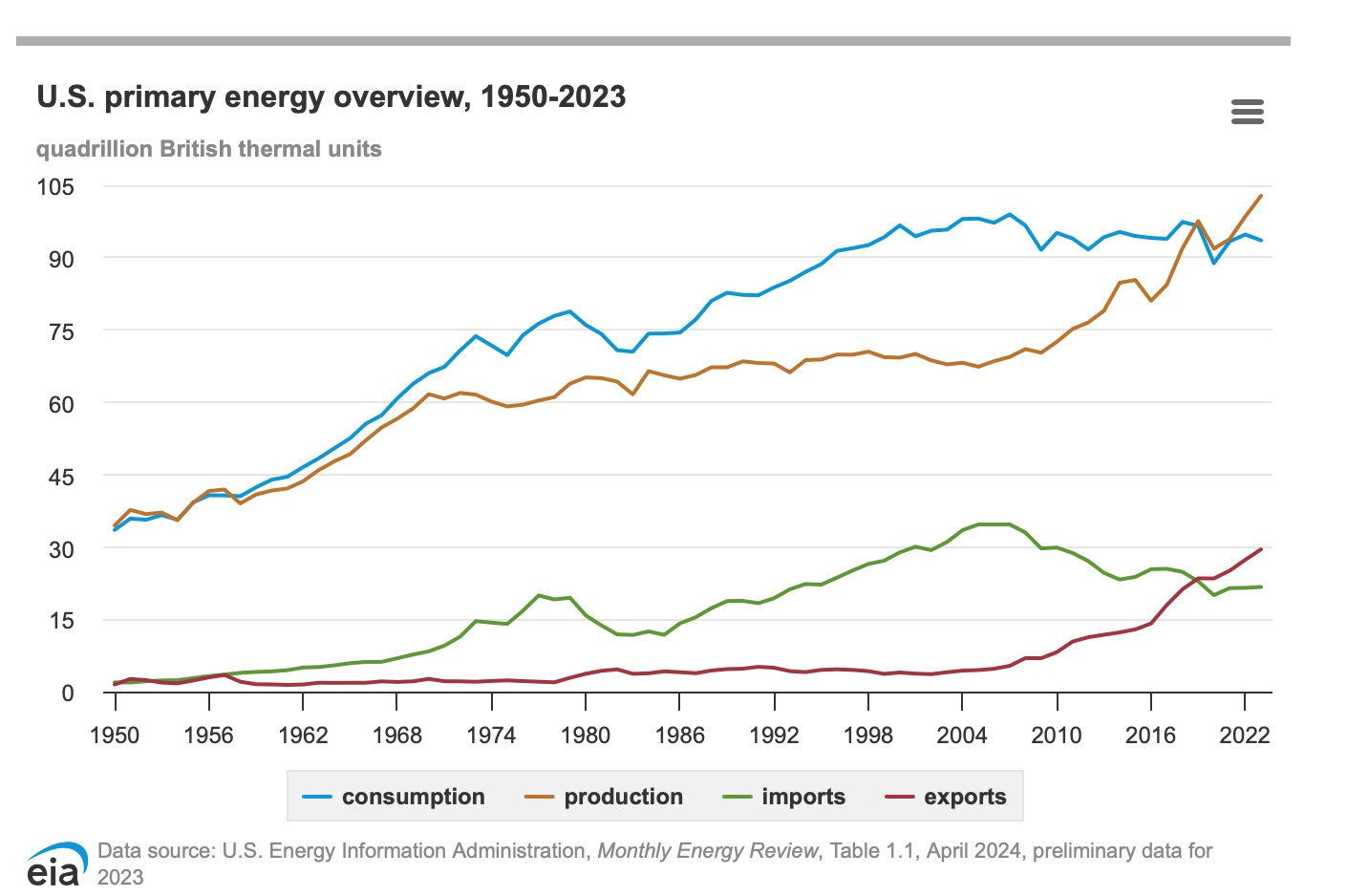

The key to remember in the following discussion is that while the US produces a lot of energy, it consumes a lot of energy - more or less break-even. Which is why prior to the shale revolution, it was a long-term importer of oil and gas - its natural state if you will.

Today the US produces about 50 million barrels per day equivalent (mboed) of primary energy and consumes 47 mboed (or about 100 exajoules or quads production to 95 consumption) - so it consumes about 95% of what it produces.

And with new oil production from shale it can trade around the edges of this large evenly balanced producing-consuming system.

Therefore it is not a petrostate as we’ll see, (its export value too small in relation to its overall economy) but it is very much a petro-culture.

Meaning, it sees its energy future inter-twined with its natural resources, and the fossil trading relationships it has built.

source: EIA

Let’s look into this in a little detail.

First the oil situation.

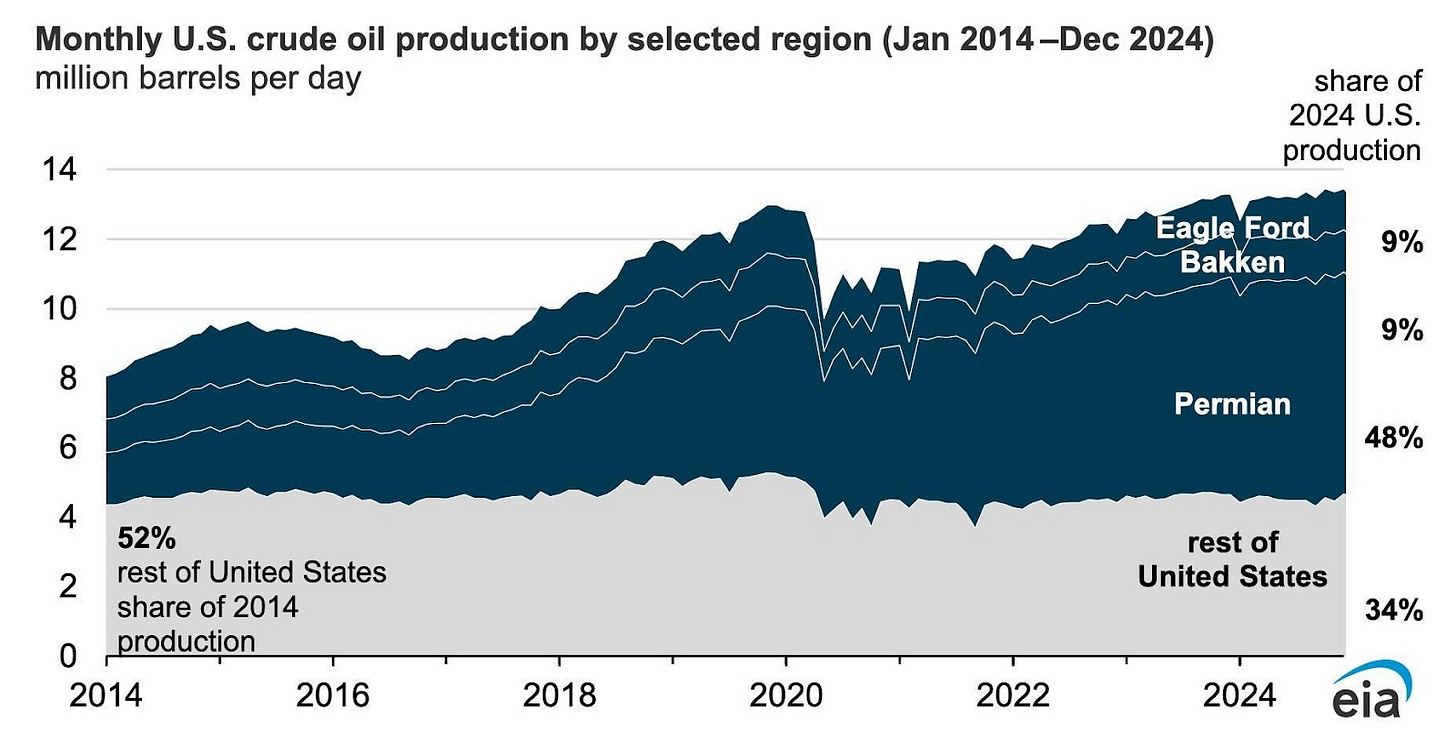

As we’ve seen (see chart) the US is a big oil producer, now the largest in the world at 13 million barrels per day.

Until 2010 it remained a very large importer - but the discovery of vast deposits of shale oil and gas in various basins across America especially the vast Permian formation located across West Texas and South-Eastern New Mexico changed the picture dramatically.

It allowed a trebling of production from 2010, and for the first time some export opportunities.

The US declared in 2019 that it was now a net exporter of petroleum products, from being a long-term importer. It is also now the largest exporter of LNG in the world.

All seems good in the US fossil fuel world with the advent of shale.

The US Fossil trade surplus is modest - and fragile

But wait - didn’t we say the US imported more crude oil than it exported. Yes.

We have to break that phrase “petroleum products” into three groups: crude oil, oil products (diesel / gasoline etc), and gas - LNG (liquified natural gas), and pipeline gas.

Crude

In crude oil, as we’ve seen, the US is a net importer. In 2023 it exported about 3.5 million barrels per day of shale crude, but imported about 6.5 million barrels crude oil a day (almost double), mostly from Canada.

Why?

As we know by now this is because although oil is a commodity, it is not a simple one.

Many refineries in the US run on slightly heavier crude oils than some of those available from the US shale formations to make the range of oil products such as gasoline and diesel that make them profitable.

They would have to reconfigure their refinery structures significantly to use more US shale oils.

But this would cost substantial investment money, it is far easier for the US refineries to import these heavier crudes to ensure their (tight) margins and balance their product sales.

Luckily for the US,close by to the north they have plenty access to (heavier) Canadian crude, so they import lots of that (see flow chart).

Oil Products

Bottom line, the US is a long-term net importer of crude oil, but using these imported crudes and strong refinery network to its advantage it is a net exporter of refined oil products (see page 34 - 35 here)

And gas - what about gas?

There are two types of gas the US trades in: it exports LNG internationally, pipes gas to Mexico and it imports pipeline gas from Canada.

Again it does this because although it produces more gas than it consumes, the numbers are pretty close and being a vast territory, Canadian gas especially allows it to keep US country-wide supply and demand in balance.

We can go through the trade flows again but the key points are that on a net basis the US is now a gas exporter: it exports LNG on top of piped gas south and imports pipeline gas from Canada in the north.

So - let’s sum all of these “petroleum products” below, this time on a financial as well as volume basis.

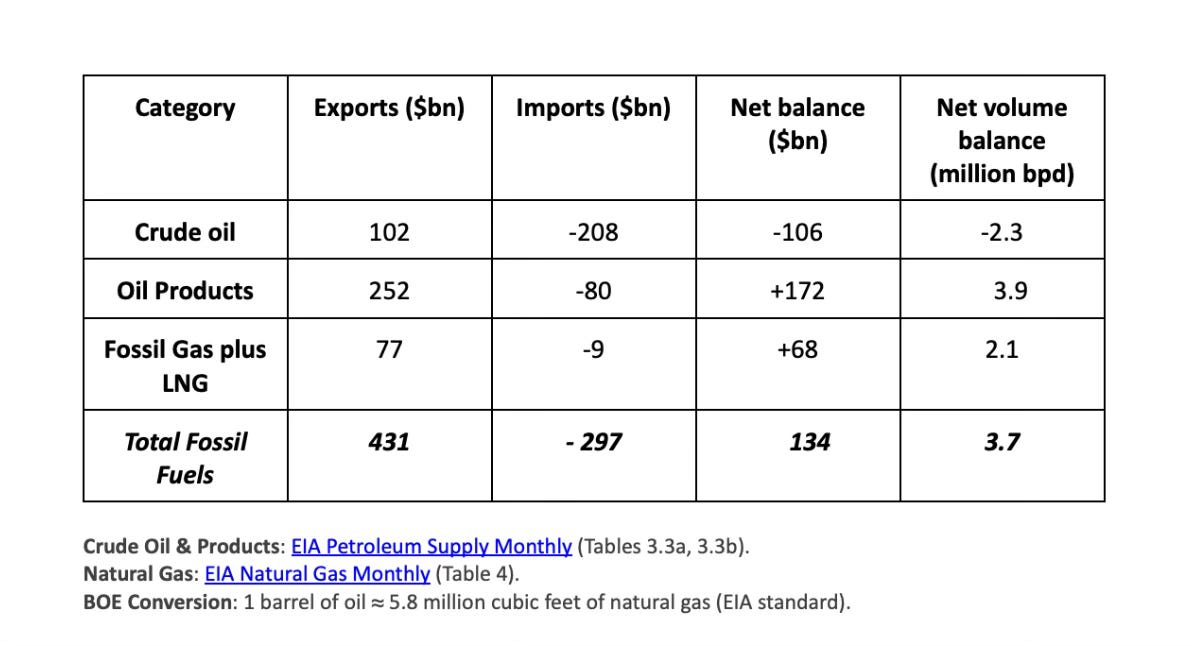

In 2023, the aggregate US fossil trading picture was the following.

Crude Oil & Products: EIA Petroleum Supply Monthly (Tables 3.3a, 3.3b).

Natural Gas: EIA Natural Gas Monthly (Table 4).

BOE Conversion: 1 barrel of oil ≈ 5.8 million cubic feet of natural gas (EIA standard).

The big picture for US primary energy is that it is dominated by fossil fuels, both production and consumption.

It does have a large trading presence, but even that today is still mostly focussed on managing its hungry internal domestic needs - and it remains as it has done from the 1920s a net importer of crude oil. Even with its recent windfall of shale oil and gas.

The strength in oil product trading continues due to large refining capacity, and new-found exports from LNG terminals adds to this trade.

Added all up, the US has a modest net fossil fuel trading balance of around $130bn pa, or about 5-6% of its total exports value of all goods and services ($2.1 trillion, 2023).

Consume, baby, consume

Historically the US has been a net fossil fuel importer - it has now become a net exporter - but only just - in dollar terms, given its exposure to high-cost crude imports.

And its domestic fossil fuel consumption remains high at almost three times the per person use of Europe and China, limiting the volume levels of exports.

As its domestic demand looks unlikely to reduce in the near-term, the US will likely remain an unstable exporter - constantly under pressure to meet local needs first before constantly finding profitable markets for its modest excess of oil products and LNG.

Despite advances by wind and solar, the US still uses over 40% gas in its power grid, having grown 10% over the past 10 years, and consumes 9 million barrels per day of gasoline, three times as much as China which has a larger on-road passenger car fleet (350 million versus 220 million in the US).

Given this heavy use of new-found mineral wealth the US consumes 10 times as much gas and five times as much oil per person as Chjina - see here, p-14.

Its export growth has been notable, but it comes off the back of import dependency on crude oil and piped gas, and on one major domestic oil production source - the large shale oil formation, the Permian, and the large Marcellus shale gas field.

The elephant slowly leaves the room: why US fossil fuel energy dominance is a myth, although renewable energy dominance remains possible

The recent move to US petroleum export growth has been made possible by the rise of the Permian oil field - now accounting for almost 50% of US crude production, in the space of just 15 years.

source - EIA

Prior to that and for almost a century the US was a very large importer of fossil fuels - up to 10 m barrels per day, and consuming up to 4-5% GDP. With no room for gas exports.

If the Permian goes into decline, the US will revert back to that prior status of larger crude oil import dependence, and lesser export potential. Economic and security concerns it had hoped to overcome will return.

When the laws of physics say no, they never mean maybe

The reservoir geology of the Permian basin is not the subject of this post (you’ll be glad to hear), although it does fundamentally matter to America’s energy future.

It is worth noting that shale oil and gas decline at rates far higher than conventional fields (2-3 times, ca 15% - 20% pa) - constant drilling is needed to stand still.

If the Permian drillers downed tools completely, eg an oil price crash as they need a constant $65 - 70 / bbl to keep going, production would fall over 80% in 3 years.

This won’t happen, but it is worth noting the narrow, fragile path US shale oil production follows.

The three biggest tight ol fields matured quickly: developed early in the 2000s, Eagle Ford peaked in 2015, Bakken in 2019, and the giant Permian growth has slowed to about 1-2% pa or lower, meaning overall US oil production is on plateau, perhaps entering decline, just 20 years after coming to prominence.

This is because the fields were drilled baby, very drilled.

Reservoir management has not been a strong feature - and the best rocks have already been depleted. Add to that government projections that suggest production will remain flat for at least the next 25-30 years - labelled as “extremely optimistic” by industry analysts and you have more a belief system about oil field strength, rather than dispassionate geologic risk management

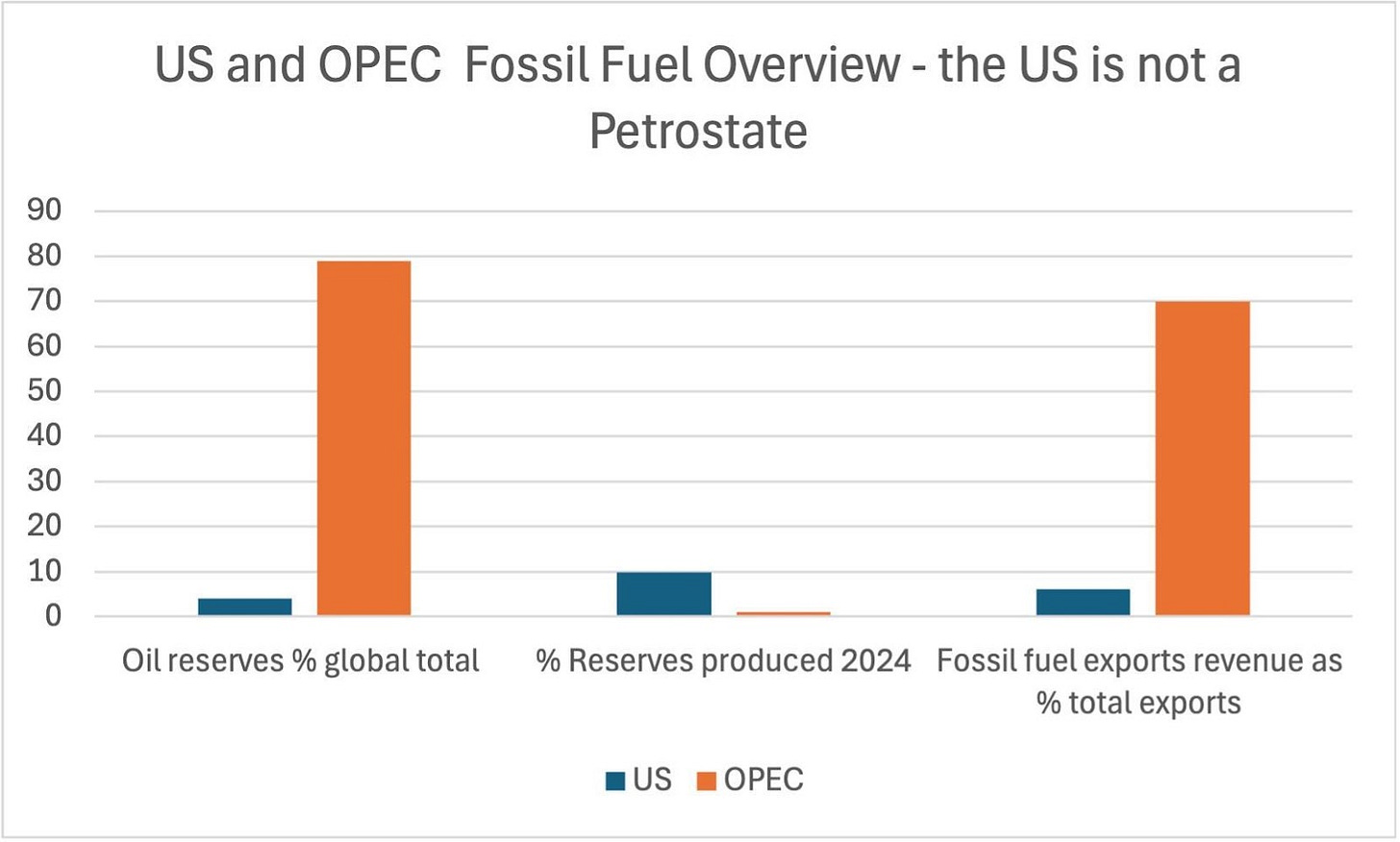

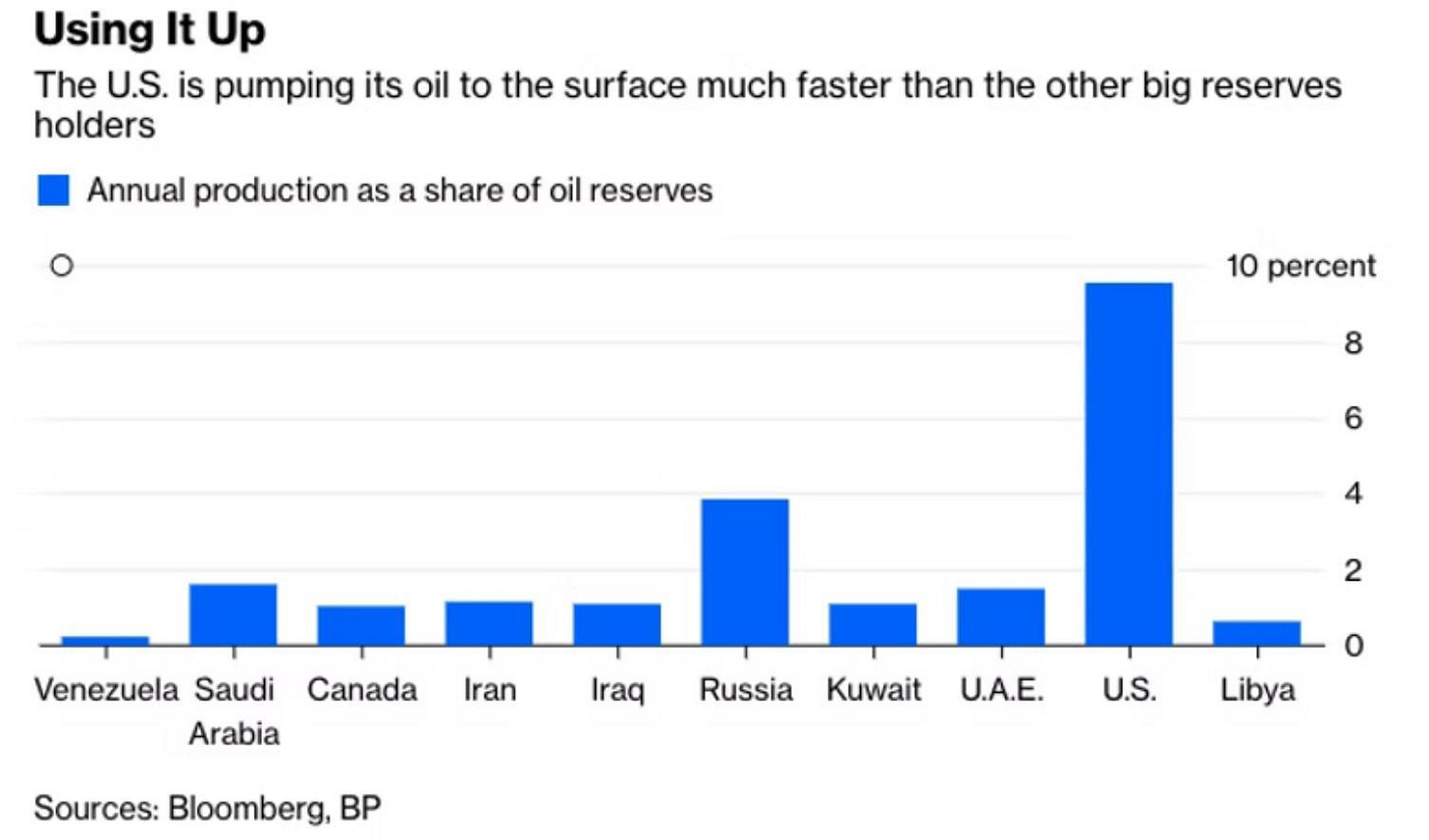

Comparing the US use of its giant fields to that of the OPEC petro-states shows the different fossil energy futures worlds they now live in.

Taking the US first:

It is home to 4% of global proven economic oil reserves, some 50-60 billion barrels - that means the total proved and developed reserves of the US are worth about $3.5 trillion dollars at $60 per barrel. Or about 10% current annual GDP. Unless replaced, with less accessible and more expensive rock formations when they are done, they are done.

Each year America produces about 5 billion barrels of oil, or about 10% of that reserve total - a simple ratio suggests production life left is therefore 10 years. New techniques can extend this, but they get lots more costly as fields mature.

And as we have noted, it manages an unexceptional $130bn surplus in fossil fuel trade: or 6% total US exports value, with crude imports offsetting oil product and LNG exports,

Then OPEC

Home to 79% global reserves (about 1.1 trillion barrels)

Each year it uses up only about 1-2% of these reserves (leaving over 75 years of production life)

And it generates 70% of export revenues from fossil fuels (ca $880bn)

As we noted due to its massive (and increasing) domestic demand - the US is not and can never be a major exporting petro-state, and hence never an external energy dominant fossil fuel economy.

It is using that reserve up far too quickly if it tries to be.

And nor should it be, as 95% of its GDP wealth comes from other sources.

It could be a dominant external energy producer of energy technology however -but as we’ll see in the second part of this note, that too is now under threat.

The bottom line: US fossil fuel consumption uses up most of its production, and that production is under constant strain.

Given this, what are America’s wider strategic energy options?

The US energy strategy choices: four fossil options and an alternative

Independence, interdependence, dominance, annexation - solving fossil fuel issues with fossil fuels runs out of road

The US arrives in 2025 with a century-long deep and nostalgic attachment to fossil fuel energy, - it partly even defines itself by its affection for the rugged fossil-fuel regalia of oil platforms and derricks, tankers coming and going at ports, nodding donkeys, giant storage depots, muscular refineries and drilling rigs and flare-stacks.

Its history has also been one using all that under-ground resource, and surface machinery and industry to aim for energy independence - expanding production at home to avoid oil security issues and inflationary price spikes from imported oil and gas.

But as we have shown in detail, fossil fuels are inherently an inter-dependent energy system, and the US is a highly active trader of fossil fuels.

With new-found access to large oil and gas fields it aims to go beyond independence or interdependence and towards “energy dominance” - via various new executive orders.

Even the annexation of Canadian oil and gas fields has been mooted as part of this strategy.

This seems however a multiplication of geological and geopolitical over-reach.

America’s oil wealth is heavily reliant on very few and maturing field formations, both of which it is drawing down at rates that will push them into near-term decline, without major investments.

Concurrently, with 10% tariffs applied to Canadian oil and gas, this will increase the cost of US fossil production, perhaps above economic sanction levels for new developments, reducing field lives further.

Tariffs in general have caused oil prices to fall to almost 20% this year to now under $60 per barrel., with for example Permian break-even prices to develop new production are around $65-70/ barrel.

Solving fossil fuel dependency with fossil fuels therefore seems to be a limiting strategy.

If we assume that major changes in US energy consumption and demand behaviours will not be a likely option given America’s petro-culture, then the US has one another choice - gradually replacing fossil fuel dependence with alternative energy sources.

After all, the IRA and CHIPS act plus tariffs recently imposed were in part to re-shore US energy manufacturing expertise and raw material access, and to strengthen alternative energy technologies such as renewables, to replace the security risk of over-dependence on fossil fuels.

If moderating large fossil energy demand is not feasible, what about manufacturing new energy supply?

2 - China’s Renewable Ascent - the world’s first electrostate

The 21st century energy paradox: only high fossil fuel import dependence creates the future route to fossil fuel independence.

In the period 2015-24 whilst US growth in energy was focussed on shale developments, the rise of renewable energy took hold globally.

Principally solar panels, wind turbines, electric vehicles, lithium-ion batteries and heat pumps.

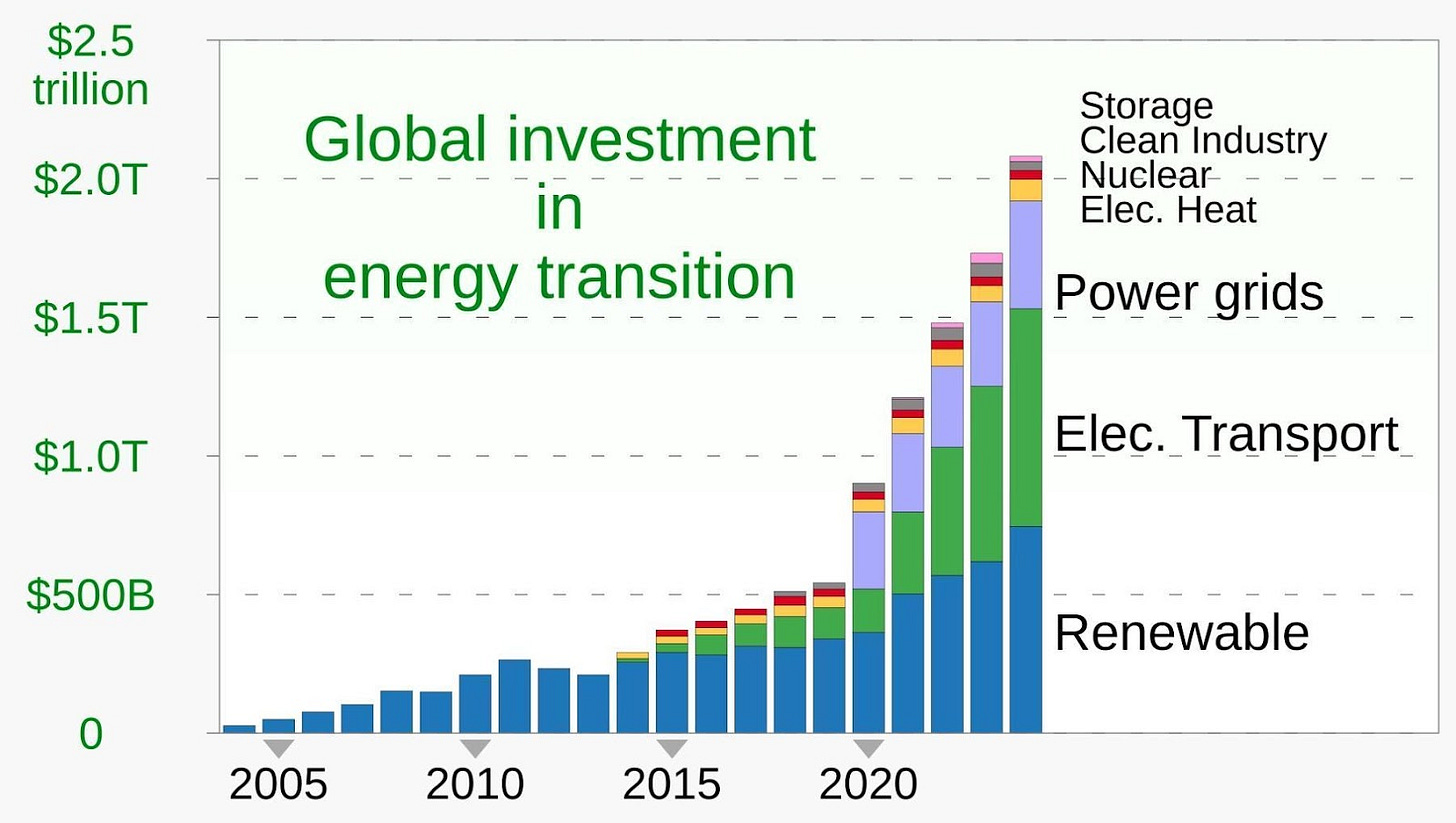

Today, in 2025, this renewable energy system invests over $2 trillion dollars per year, compared to the oil and gas industry’s $500 - 800bn, more than double.

It is also growing at over 15% pa, meaning by 2030 the investment could reach over $4 trillion annually, whilst oil and gas investment stagnates around the $500-800bn mark pa.

The global EV market alone is growing at 20% pa generating new sales revenue of $650-700bn per year - by 2030 this sector alone could be worth $1.5 trillion in sales annually.

Note global crude oil sales weigh in at $2.3 trillion pa, so this EV sector alone nearly matches that revenue potential, and at these growth rates will surpass it by 2035.

The largest investor now in renewable energy is unsurprisingly China: unsurprising because it runs a large fossil fuel deficit of about $400bn, or about 17% of total imports, or 3% of its GDP.

It could take the route of the US and attempt to exploit its limited fossil reserves, reduce demand, and diversify supply.

But now with the advent of mass scale renewable energy technologies, it has decided via a strategic state planning process to rebuild its energy system bottoms up.

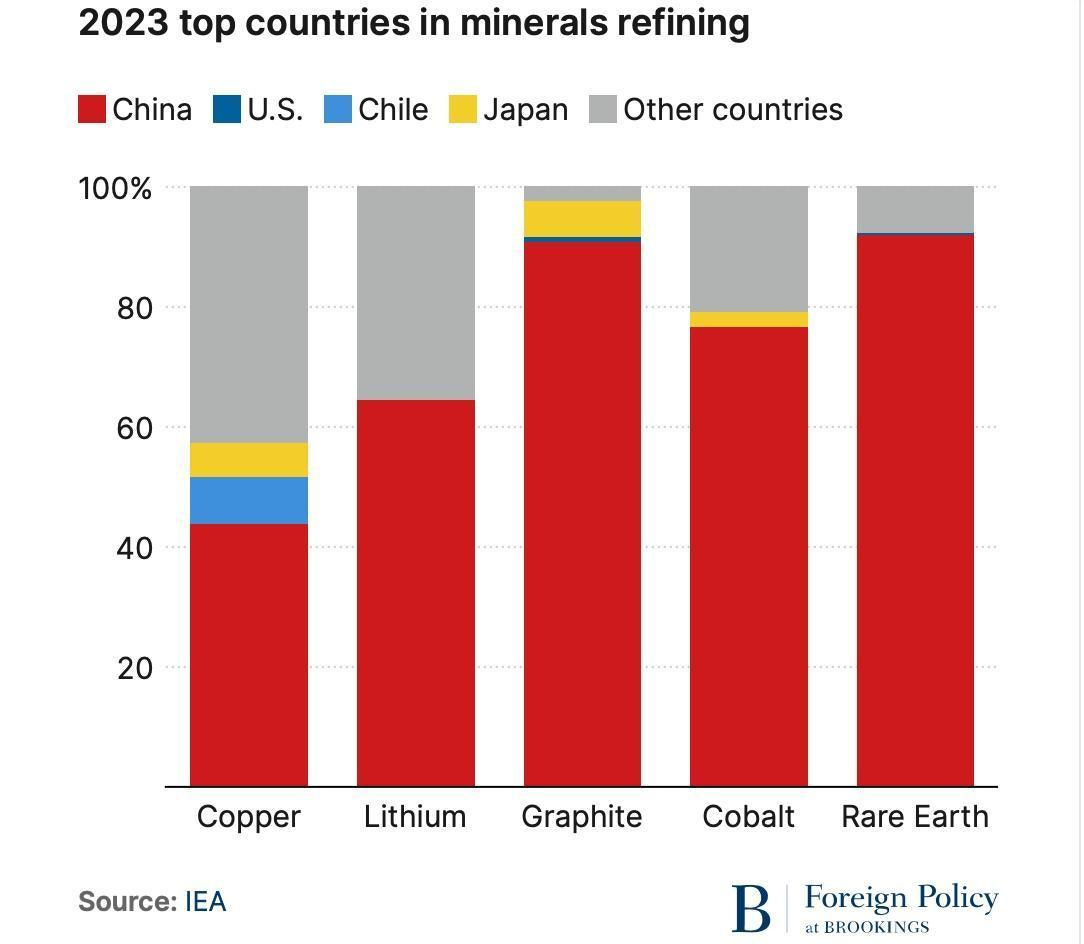

Literally - as it commands a large market share (40-90%) not just in raw minerals, but more importantly the upstream refining process to generate key manufactured products materials eg transforming lithium into lithium carbonate or lithium hydroxide.

Opening a lithium mine is routine, developing an economic lithium refining process with supply chains is more complex and creates a lasting technological lead.

The US by comparison has a very small presence in such materials and technologies and manufacturing ecosystem development.

Whilst China retains coal as a base-load energy source (unfortunately for emissions targets), it is now rapidly installing sharply-increasing amounts of solar, wind, battery storage and electric vehicle technologies with its value chain lead in materials and manufacturing expertise.

In the power sector alone wind and solar make up over 21% of power generation (gas is 3%), growing at 15% per year - meaning by 2030 it will be close to 40% of the power grid.

Cliche as strategy: necessity invents

For large importers of fossil fuels - the only way out is to rebuild your energy system without fossil fuel dependence - not out of duty, not out of moral priority, and not out of even long-term climate issues, but by sheer self-interested recognition of building a cheaper, better energy system that is endurable, profitable, and growing ever better and more innovative.

With a large and economic fast-growing renewables sector, high fossil fuel import dependence provides the motivation to develop a renewables industry, or at least create an import strategy for renewable tech.

One that can replace fossil fuel dependence barrel by barrel, TWh by TWh, exajoule by exajoule, exchanging energy demand molecule by molecule with electron by electron.

All this highfalutin analysis ends in cliché: necessity is the mother of invention.

Clearly this plays to China’s manufacturing strengths: it has limited reservoirs of oil and gas, but it can build massive stocks of home-built energy in PV panels, wind turbines, and lithium-ion batteries.

And it has.

The rise of the electrostate … and a second cliche: China the Saudi Arabia of renewable energy

By last year China was domestically generating about 2,000 TWh of electricity from wind and solar alone: that is the equivalent of about 3 million barrels per day of oil, growing at 15% pa. Displacing that fossil fuel amount from its grid.

As China builds out its renewable technology, it can also begin to export it in parallel as it quickly overcomes domestic demand.

It can also attain very high market shares in renewable technology quickly - large-scale manufacturers can access lower costs through major deployment, reducing costs further in a beneficial loop of learning curve efficiencies.

This is not theory - this is on the ground reality: China has the lowest cost BEVs in the world, the lowest cost solar panels and the lowest cost lithium-ion batteries: those batteries for example having reduced in price since 2015 by 85%, at a compound annual rate of 15% reduction.

And now dominated by two Chinese firms (CATL and BYD) with over 60% market share of a $200bn pa market sector, growing at 12-15% pa.

China has the highest global market share in exports of all these technologies: solar panels, EVs, and batteries. From practically a position of zero market share in 2010.

It is little surprise that given its motivation, manufacturing skills, and strategic investment in the supply and value chain of renewables from mine to manufactured product and export channel, China now essentially dominates renewable energy technologies.

Its trade surplus of $195bn is actually similar to Saudi Arabia’s trade surplus in oil and gas, $310 billion - except China’s surplus is growing at 15% per year, whilst Saudi Arabia’s growth is yoked to the vagaries of world oil prices.

And China’s energy tech surplus as a % of its annual exports ($ 3.4 trillion) is only 6% with a very high ceiling, whilst Saudi’s exports make up 70% of its total export value, running close to its limit.

Two giants in world energy now: the traditional petrostate, and the fast growing electrostat

The US and China energy gap widens - working in two different centuries

Let’s take stock of this change now and compare China’s energy strategy with that of the US efforts in renewable energy.

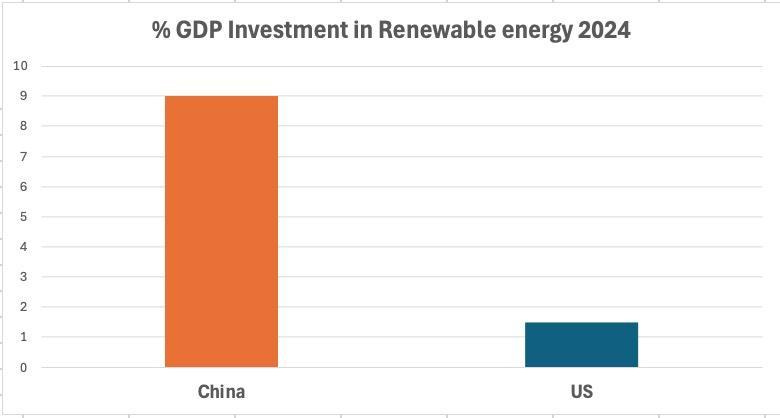

Latest analysis notes the input of of renewable industry to economic contribution (GDP) in China is 9-10%, in line with its strategic goals, whilst in the US it is 1-1.5%, with the majority of energy input to GDP still fossil fuels (ca 5-6%).

China outspends the US in renewables in a ratio of about 6:1 ($890 bn pa versus $140 bn).

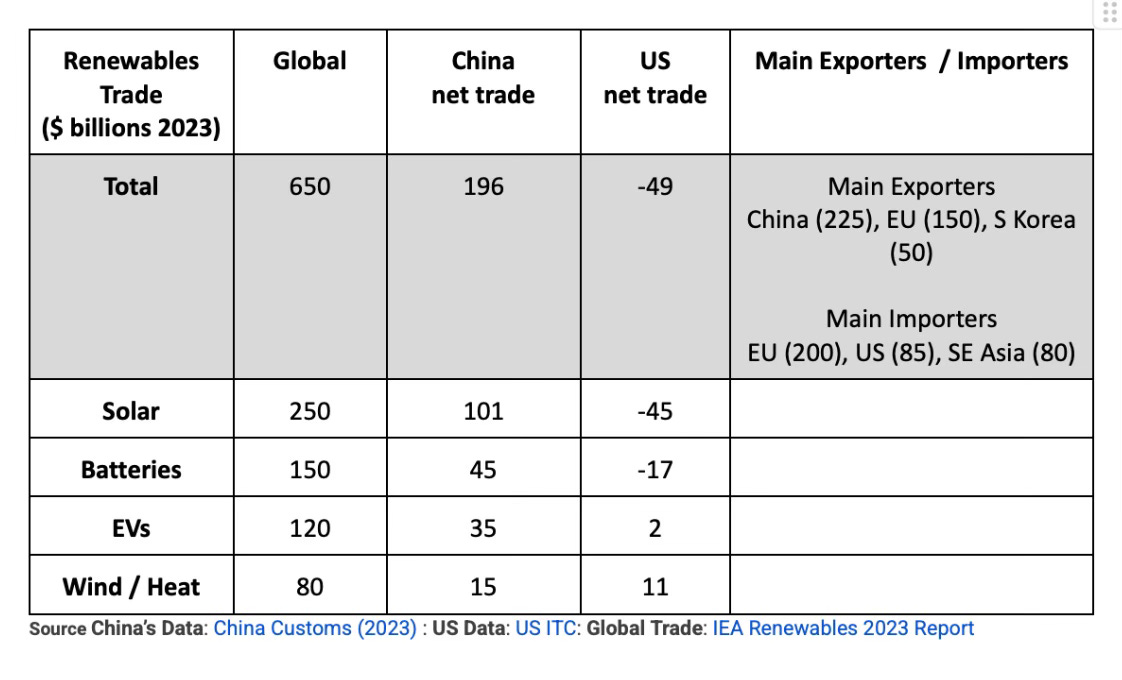

This manifests already quickly in the trade figures for renewable technologies:

Renewables Trade

Source China’s Data: China Customs (2023) : US Data: US ITC: Global Trade: IEA Renewables 2023 Report

In chart form this shows the very clear distinction between China’s energy strategy and priorities and America’s. Note this is the trade of China and US globally, not directly - but there is considerable overlap.

Key Takeaways - China

Renewables Surplus: China’s renewables trade surplus hit $195bn, or about 6% of its global export revenue. Marking the creation perhaps of the world’s first energy electrostate.(see first coining of this reference here by our colleagues in Ember) - it can be defined as “a nation whose economy and geopolitical power derive from renewable tech dominance”.

Global Renewable Market Leadership in products:

Solar: 80% of global panel production (LONGi, JinkoSolar).

Batteries: CATL / BYD control 60% of global lithium-ion battery supply.

EVs: BYD sold 25% more electric vehicles than Tesla in Q1 2025 globally, becoming market leader for the first time

Key Takeaways - America

Renewables Deficit: : The US renewables overall deficit was about $50bn, or 2.5% of total exports. It held a small surplus in EVs and wind - but EVs are mostly dependent on a single brand (Tesla), and pro-wind policies are being reversed in certain states.

Global Renewable Market import dependency in key products

Solar: strong reliance on imported panels and technologies

Batteries:heavy reliance on imported technologies from China / SE Asia

EVs: main brand is Tesla, which is losing market share, and outside the US has limited growth options, limited product developments

In sum - China is taking a strategic approach to dismantling its reliance on fossil fuels (other than home-grown coal which is under a managed exit plan), by manufacturing new renewable energy technologies and products.

Its $195billion trade surplus in renewables is already wiping out 50% of its energy import reliance on fossil fuels, and with trade growing at 15% per year it will completely over-turn it in the next 2-3 years. Beyond that, it moves into high growth energy surplus - delivering long-term energy production to its trading partners, and avoiding the daily imbalanced dependencies that oil and gas trade always bring.

Neither a renewable power nor a petro power: America’s energy strategy is increasingly confused

Meanwhile the US is investing further into fossil technologies, at the expense of creating any strategic vision for renewable energy industry development.

The US does have investments and expertise in renewable technology - its grid is already 15% powered by wind and solar.

But

Its CHIPS act and IRA initiatives notwithstanding (aimed at stimulating domestic renewable technology development, but now being gradually dismantled) the current administration continues to believe more in fossil fuel development and is hostile toward wind projects and EV partnerships and developments (still relying heavily on Tesla).

Energy is a serious business, governed by thermodynamics, physics and engineering: it does not respond well to sentiment and emotion

On this trajectory the fast-approaching energy conundrum for the US is the following:

in fossil fuels a looming reversion to wide-spread and permanent import dependence, especially oil, unless it reduces demand - it cannot rely on the Permian or Marcellus forever

in renewable technology an equally chronic dependence on technology imports – which unlike fossil fuels, will require a major increase in energy supply investment

Yet - on current policy, the energy strategy appears to be the reverse and quite emotional – a sentimental desire for increased fossil fuel investment and demand, plus an instinctive dislike toward renewable manufacturing supply.

Emotive tariffs will do little to enhance fossil fuel supply, as it is already heavily domestic focussed – it can only force prices for any imported components upwards instead, threatening the fragile shale production ecosystem

And tariffs are unlikely to help domestic manufacturers set up local production in renewables (dependent on component imports), or work with foreign partners who will be reluctant to invest in an unpredictable economic situation and behind erratic tariff paywalls.

Even if there were now a strategic, disciplined desire to establish renewables manufacturing in the US, the pace of renewable energy development is now so fast that creating a competitive domestic industry with export capability seems increasingly low probability – for now, and even into the longer future.

And for America this is not just an increasing dependence on energy imports for renewable tech, it is the simultaneous loss of a massively increasing industry growth opportunity, whilst causing inflationary energy forces at home.

Putting all this together shows in plain sight two major energy economies beginning to separate their energy paths for the rest of this century.

Whilst America now grapples with managing its supply - demand balance in terms of fossil fuel imports and exports, it is now also rapidly losing ground in parallel to the renewable tech energy sector being built around it.

3 - US Energy Choices: Petro Culture vs Energy Tech Leadership

Conclusion: For America, a Fragile, Reactive Energy Future

In energy terms the US is neither a petrostate nor like China, a rising electrostate.

After all the sound and fury of its energy statements, it signifies only break-even in energetic terms when you subtract renewable energy deficits from fossil fuel surpluses.

Source China’s Data: China Customs (2023) : US Data: US ITC: Global Trade: IEA Renewables 2023 Report, OPEC

OPEC and China have chosen their paths and played to their strengths: huge net fossil fuel reserves, and huge manufacturing scale and expertise respectively.

The US has not chosen a singular energy vision, beyond maximising the transitory resource excess of shale production, now in effect one remaining large field formation.

If America has an energy strategy, it is a blend of its long-term affinity to fossil fuel investment preferences now mingled with widespread tariffs to suddenly re-invent renewable technology - but undermined immediately by demonstrative trade tariffs.

Both feel built on sand.

The sentimental energy giant

The reality is that in the US fossil fuels do not objectively impact GDP or trade surpluses, but energy consumption subjectively shapes its economy and culture - a "petro culture", a sentimental attachment to oil and gas infrastructure, without the rock-solid reserves to allow it to derive petro-state style revenues.

Meanwhile its deployment of renewables tech has been haphazard and prone to political shifts and changes. Now including punitive trade tariffs on foreign technologies and major trading partners.

It is now also tactically using tariffs to excite investment in the US to create new energy technologies - yet even then with a nod and a wink setting policies at state level that aim to support fossil fuels at the expense of renewables,( eg mandating gas plants to be 55% of new energy project sanctions in the renewable-leading state of Texas.)

Without faster innovation and international collaboration, the US risks losing ground in the global energy transition.

China’s dominance in renewables manufacturing and OPEC’s oil market control could marginalize US energy influence unless it leverages its tech and financial strengths.

Without rapid scaling of renewables, the US risks energy insecurity as fossil reserves decline.

This could increase reliance on fossil and renewable imports (e.g., lithium for batteries, critical minerals) and with higher energy prices force austerity in energy consumption.

If the US abandons strategic reforms, neglects renewable manufacturing, and maintains high tariffs over the next 1-2 years, the outlook will be shaped by economic strain, energy security risks and technological isolation.

Economic Strain

Rising Energy Costs:

Fossil fuel dependence would deepen as renewables deployment stagnates. Depleting domestic reserves (e.g., shale oil/gas) and global volatility (e.g., OPEC+ supply volatility, geopolitical conflicts) would drive up energy prices.

Households and industries (e.g., manufacturing, transportation) face higher costs, eroding competitiveness.

Trade Deficits Widen:

Declining fossil exports (due to shrinking reserves) and persistent reliance on imported critical minerals (e.g., lithium, rare earths) for limited domestic renewables would balloon trade deficits.

Retaliatory tariffs from allies/competitors (e.g., carbon border taxes) could further isolate US exports.

Job Market Polarization:

Short-term gains in fossil fuel sectors (e.g., oil/gas drilling) would be offset by long-term losses as global markets pivot to renewables.

Auto manufacturing could collapse if US EV development lags behind China/Europe.

Energy Insecurity

Fossil Fuel Dependency Trap:

The US would become a net energy importer again by 2028–2030 as shale reserves decline. Reliance on OPEC+ or Canadian/Venezuelan oil would resurge, recreating 1970s-style vulnerabilities.

Global Green Tech Race Lost:

China and the EU would dominate renewable tech (solar, batteries,), controlling 80–90% of global supply chains. US tariffs would make imported tech (e.g., Chinese solar panels) prohibitively expensive

Domestic innovation stagnates due to underinvestment and isolation from global R&D networks

Missed Industrial Opportunities:

Industries like EVs, battery storage, would cede market share to foreign competitors. By 2028, Chinese automakers (e.g., BYD) could dominate global EV sales, while US legacy automakers shrink.

But - that is a logical treatise and assessment.

Checking out, but never leaving

Another way to approach this is that the US is willing to cede such leadership, and low-cost energy development, but retain its nostalgic, sentimental attachment to its oil and gas culture and norms.

It may assume it can deal with receding influence in energy leadership, as long as it can dominate certain sectors such as oil products, and regularly publicise new large fossil energy projects eg in LNG where it does lead world trade, albeit in a niche sector, in a low-margin part of the fossil fuel industry.

That seems a poor financial, economic and technology bet for future generations, but it may make America feel comfortable in contemporary energy choices.

An economic giant going into industrial energy torpor, shuffling down an energy road toward a dead end.

Which will be a very big risk, as other energy giants pursue very different visions.

For in energy, you can check out any time you like - but you can never leave.

Note - all my work on substack is my own, and does not necessarily reflect the views of any company I work or deal with

Will we see a day when conserving fosil fuels and investing in renewables is seen a patriotic?