The Seagull

The car that signals the energy transition is fast underway

In May this year BYD the leading manufacturer of BEVs on the planet launched a price cut initiative (up to 34% reduction) dropping the selling-price of its best-selling hatchback the BYD Seagull (Honor Edition) to $7,700 in the Chinese domestic market.

This means that car (as of May 2025) that iconic vehicle now undercuts not just its rivals such as

- The gasoline Toyota Yaris ($15,000),

- or its challenger Chinese EV the Wuling Bingo ($9,000)

but also a mid-spec 16 inch MacBook Pro (Space Black) laptop computer, with 4TB of storage and some screen enhancements ($7,850).

It has often been said that EVs are just laptops on wheels.

Well, if you added some wheels to a 16” MacBook Pro, that would then be even more expensive again than the BYD Seagull, would roll a few yards after a push, and not do much more mobility-wise: versus a brand new family passenger car that has a single-charge range of over 250 miles (400 km), and same price.

But.

This is a much more significant move than just EVs just getting cheaper yet again.

Let’s widen the lens to show how this indicates how energy in the world transport market has now suddenly changed – a trend we predicted in some detail here this month.

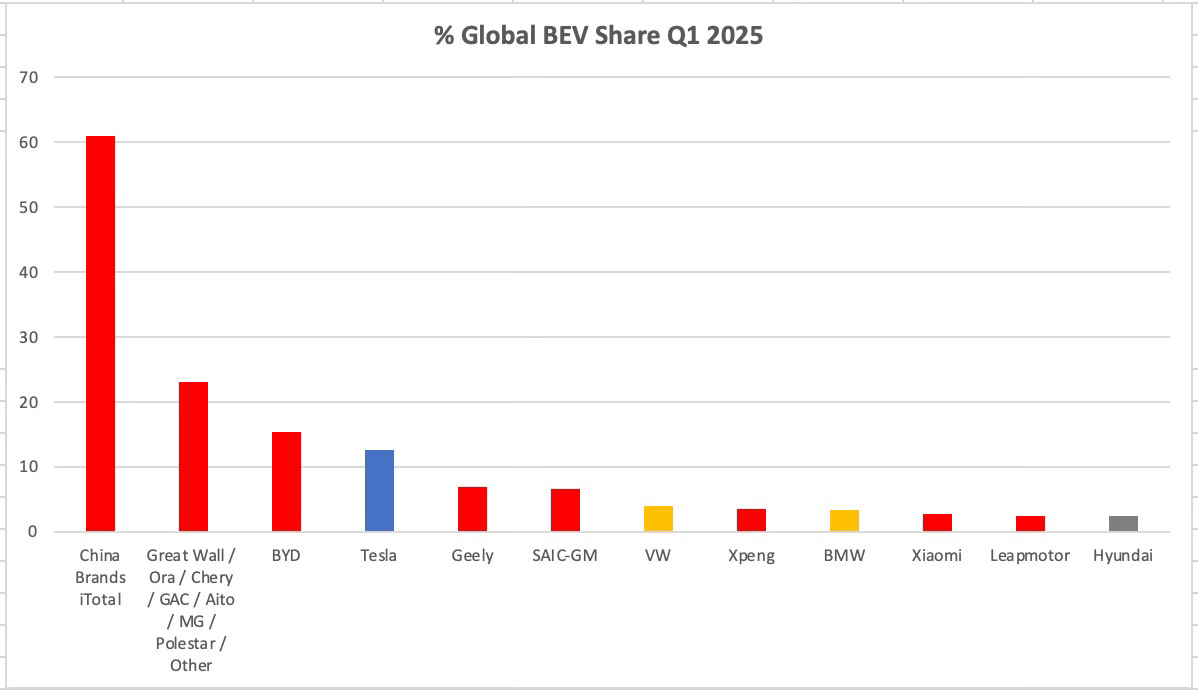

As of Q1 2025, this is the global market share of EVs, according to CNEVpost and Trendforce, with the addition of the origin of the brand added (red for China, blue the US, yellow EU, others in grey)

source: CNEVpost, Trendforce

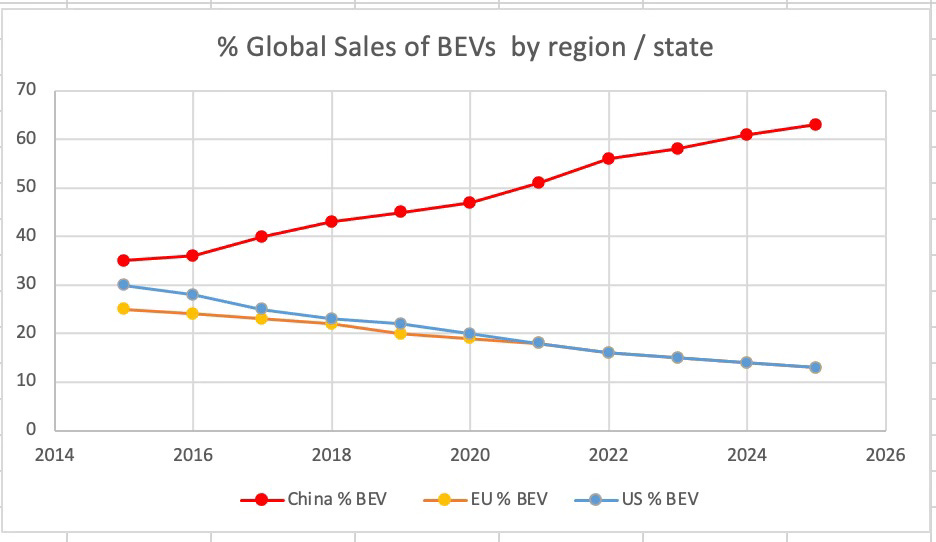

This is remarkable enough, but widen the lens now further in time, and look at the trend in this growth of Chinese brand dominance

source: BYD annual reports, CPAC, Schmidt Automotive, CNEVpost

Chinese brands, led by BYD, now make up 60% of global EV sales.

And this matters a lot, as EVs make up a very fast-growing segment of world car sales.

EV sales are quickly outgrowing global car sales of all other types: gasoline, diesel, hybrids. Not yet in absolute terms, but quickly getting there too.

From less than 1% of car sales in 2015, EVs are now 20% of global sales of cars, one in five, growing at 20% per year.

Meaning they will possibly be 50% (or more) of all new car sales within the next 5 years.

And in China, the largest car market in the world, home to 60% of all EVs manufactured on earth, EVs will likely be 50% of all vehicle sales by the end of next year.

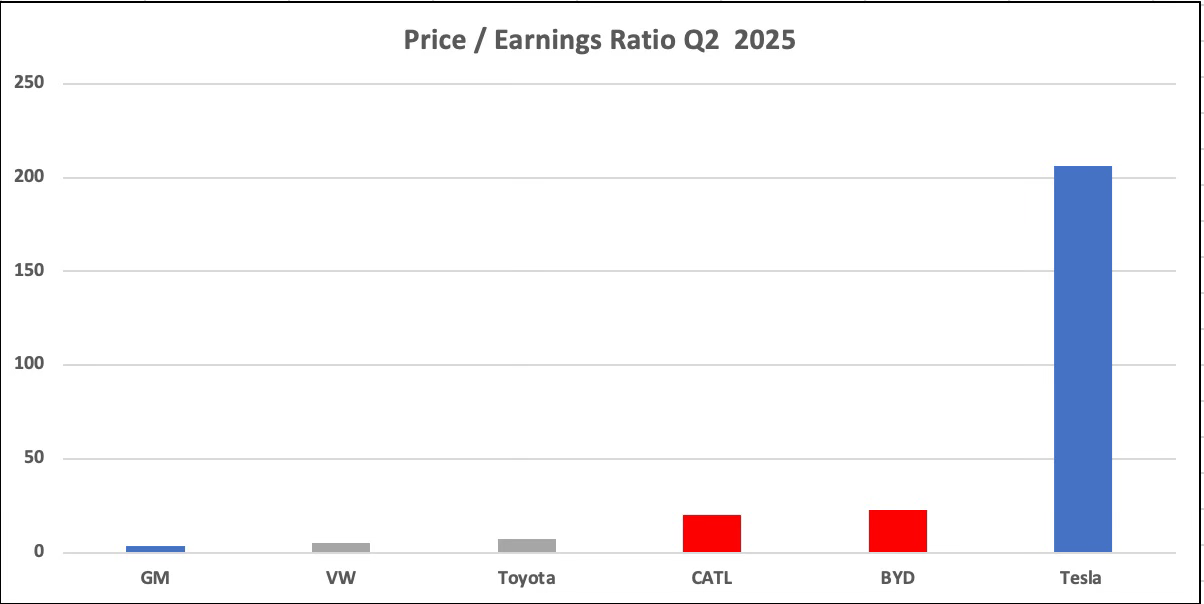

Price / earnings (p/e) ratios of current large automakers and EV and EV battery makers give a financial market guide of what they think are the prospects for companies in the future (the higher the ratio typically the better the prospects – but note this is just one metric and it has its flaws)

source: Bloomberg, google finance

Pause - This note is not an investment advice column, but you might want to do your own head-scratching and analysis of a least one stand-out brand in this chart, and also consider how traditional fossil car incumbents are doing versus Chinese EV brand new entrants.

The bald p/e numbers suggest scepticism on the legacy ICE-to-EV transition, a modest reflection on the Chinese EV growth, and a high premium for Tesla’s autonomy strategy.

But readers should of course make their own decision.

Sea Creatures

Why the sudden rise in the Chinese automotive sector, especially BYD - who name their cars after sea animals due to fluidity and intelligence.

For over a decade now China nationally has pursued a “NEV” (new energy vehicle) policy, subsidised brands like BYD, and now sees the massive market return of this effort.

If BYD sells its target of 5.5 million EVs this year, that will be revenue of over $200 billion accelerating at 20-25% pa.

As transport moves to electrification China moves its leading electric device manufacturing skills to cars.

If we extrapolate current trends to 2030 (or even just 2028) Chinese brands will make up over 70% market share for EVs.

National policy, integrated battery technology, low-cost models to allow new market developments eg in SE Asia. Latin America and Africa, make China the dominant force in world electrified transport.

And not just cars – it is the leading brand in electrified buses and heavy-duty transport.

The Seagull was the prototype of this low-cost entry EV for the world market, while Tesla remained at the elite / luxury level, and the EU looked down on EVs as concept cars, not mass business revenue options.

Beyond the wall

The China dominant EV trend looks sustainable, even if the EU and US cut themselves off via tariff paywalls

Tariffs in theory are used to allow domestic industries to gain skills to compete globally.

But if there is no unified strategy of EV development, limited skills behind the wall and supply chains part cut-off too – then it is just closing off access to cheaper and better-quality goods.

That wall is however already breached: BYD is now 20% of the EU market, and consumers will see the cheaper, better EVs parking up below the hastily closed gates.

The EU is already working a JV model of strategic surrender via its various partnerships such as VW-Xpeng and localised production via BYD in Hungary.

While in the US – with Tesla’s decline and loss of global scale, and political EV reluctance meaning no competitive EVs to sell – there seems to be a strategy of self-imposed EV irrelevance.

Whilst the Tesla leadership has focussed on politics, AI, robotics and Mars colonisation there have been zero new mass market Tesla EVs since 2020.

Meanwhile Wang Chuanfu’s mantra for BYD has been: “we focus on making EVs cheaper, better, faster.”

And so, The Seagull

This clever little BYD hatchback may or may not survive the ever-evolving and expanding BYD model range – but the 2025 BYD Seagull Honor Edition will have its place in history beside the Model T Ford (and it is available in more colours).

It is the car that showed that mass-produced quality EVs can be made so affordable that they can knock fossil fuel cars off their transport perch and herald a world energy transition in transport - 25% of global energy use, and so forcing oil demand into decline.

It shows that global consumers can now have access to ultra-cheap EVs and that China's EV dominance isn't just about price, but systemic advantages: vertical integration, battery innovation, and policy consistency.

And it results in better global energy consumer choice, especially in regions eg the Global South that have often been by-passed in energy innovation, or left to the latter margins.

The US/EU responses—EV tariffs without competitive solutions—are unlikely to succeed in stopping this trend. And in fact may lead to their own product stagnation.

In the US in particular, GM and Ford are essentially pension funds clinging to ICE mark-ups, their time to enter the new EV technology space likely gone - and any escape hatches –tariff repeal, Chinese JV mandates – now shut.

The US is retreating back into 10% of the global car market behind a wall - and the low-cost <$25k Tesla “Model 2” EV has never appeared – but now what would be the point of it? Who would buy it in the US? How could Tesla scale to make it profitable locally or globally?

A bell rings

We often search for logical, rational mathematical signs of transition - peak emissions or demand declines. And this is all well and good.

Yet also hoping for a bell to ring to signal “the change is here!”

We may just now have that moment.

When a $7,700 high quality EV car emerges, cheaper than a lap-top, a 30kWh mobile storage unit as well, in 2025, with 75 years of this century to run (at exponential rates of growth and price improvements), it is difficult to avoid the idea we have crossed an energy threshold, where complacency cedes almost overnight to disruption.

We don’t need our spreadsheets on this day to declare transition: we only need to look at the Seagull, and note the energy change it represents, made real.

And -

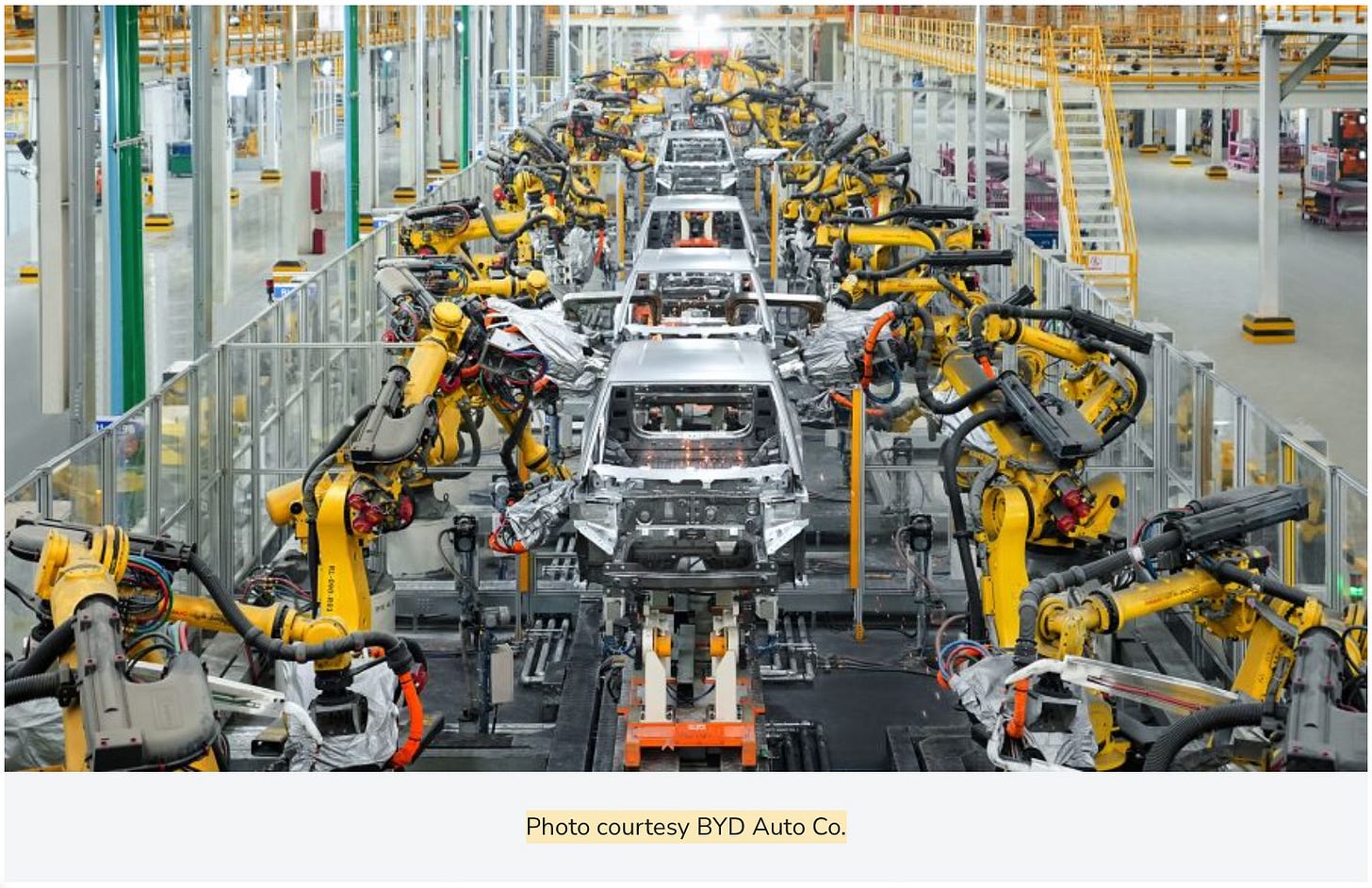

While you read this short piece, another 12 Seagulls rolled off the production line - here she is.

Note – throughout this note, EVs refers to 100% battery EVs only – we don’t do tailpipes in this analysis.

Great post. Given the developments you outline here. How do you assess global oil demand compared to mainstream forecasts such as the IEA. Do you see them as being largely correct or do you think they're underestimating the impact on oil demand? Thanks